In this exploratory essay, first-time FreakSugar contributor Matthew S. Altobell takes a deep dive into director David Lynch’s sometimes-misunderstood film Wild at Heart.

For more from Mr. Altobell, go to his website, www.mattaltobell.com, and be sure to check out his Patreon page!

Surfaces and Depths: An Appreciation and Analysis of David Lynch’s Wild at Heart

Introduction

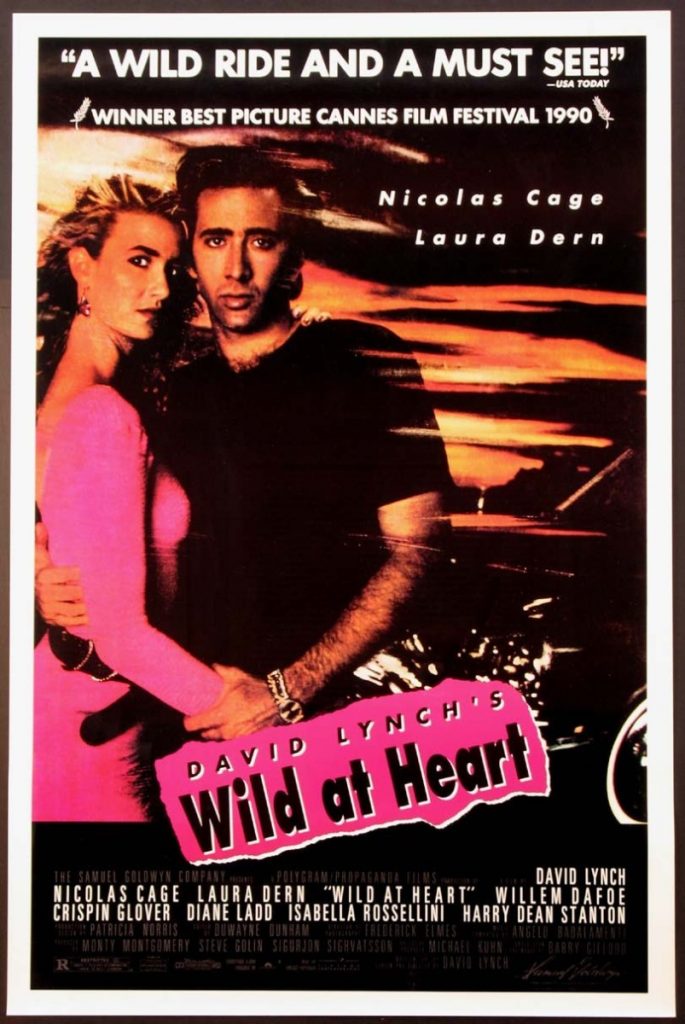

Three decades after its release, Wild at Heart remains David Lynch’s most disagreed upon film and, arguably, one of his least understood. Arriving on the heels of the immensely popular first season of Twin Peaks, the film puzzled critic and audience alike during the Cannes film festival before unexpectedly winning the Palme d’or. Mainstream audiences, too, were unsure what to make of the film, its glitzy postmodern cuteness seemingly at odds with the noir trappings of Twin Peaks or the pathos of The Elephant Man, let alone the thumping industrial darkness of Eraserhead and the rich textures of Blue Velvet. While critical hindsight has come to embrace such erstwhile objects of scorn and dismissal as Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me and Lost Highway, Wild at Heart remains seldom revisited. The consensus seems to be there is no point in looking for profundity in something so obviously shallow.

At first glance this is no wonder. Lynch’s most excessive film all but dares us to take it seriously as it skates on the thinnest of ice, appearing to value the cheap and cute over the heady depths we expect from its director. The nostalgic appropriations of 1950s pop culture and the on-the-nose references to The Wizard of Oz sit uneasily beside the grotesque characters, hideous violence, and explicit sex. The hysterical pace and narrative composition continue to baffle, and even now the paper-thin characters and discursive plot hardly seem the logical progression from the deliberate and focused author of Blue Velvet. Closer analysis, however, reveals that these are surface level schticks, a winking director testing a new manner of sleight of hand for delivering more covert messages and conveying deeper themes.

The film centers upon Sailor Ripley (Nicolas Cage) and Lula Pace Fortune (Laura Dern), two young lovers who can only find relief from an ugly world in each other’s arms. The film is bookended by Sailor’s two stints in prison, and between them Lula’s mother, Marietta (Diane Ladd), places a contract on him to be killed. The couple hit the road and along the way, we learn some hideous secrets and macabre details of Lula’s family history as we encounter a whole Night Gallery of creepy cousins, fiendish henchmen, and grotesque villains from every point along the Lynchian spectrum of ickiness and decay.

The Lynchian Metaverse

It is worth noting that the scene-stealing/chewing Diane Ladd (who received an Oscar nomination for her effort), is in fact the real-life mother of Miss Laura Dern, who portrays her daughter here. It is worth further noting that in the film, Sailor’s most prized possession is his snakeskin jacket (a “symbol of [his] individuality and [his] belief in personal freedom”), which is Cage’s homage to Marlon Brando’s character in The Fugitive Kind, a 1959 film directed by Sidney Lumet which in turn was based on a Tennessee Williams play called Orpheus Descending. Yet another intertextual note: it was during the production of said play that Diane Ladd met Bruce Dern, resulting in the conception and eventual birth of one Laura Dern.

Wild at Heart includes more than the usual number of performers cross-pollinated from other Lynch projects. In addition to the casting of Dern, her Blue Velvet co-star Isabella Rossellini turns in a truly bizarre depiction of the wonderfully named hitwoman Perdita Durango. Harry Dean Stanton also makes his first of many appearances for Lynch as the lovable and ill-fated Johnnie Farragut. But the most significant source of inter-oeuvre actors is the concurrent television phenomenon of Twin Peaks. (Wild at Heart was released between seasons one and two, at the height of the show’s cultural and popular appeal). Sherilyn Fenn makes an unforgettable appearance as Sailor and Lula witness the wreckage of a surreal car accident (the music in the scene is oddly reminiscent of that in Twin Peaks.) Grace Zabriskie portrays a grotesque henchwoman who derives sexual satisfaction from ritualistic murder. David Patrick Kelly seems underutilized as the only member of her gang not dressed for Mardi Gras. Frances Bay projects a quiet menace as the master of ceremonies during a dinner scene where contract killing is the special of the day. Jack Nance appears out of nowhere as a campy rambler who unsettles everyone by talking about his dog. The bank president from the season two finale drops in for a brief cameo as hotel staff. But, justifiably, the most famous Twin Peaks guest moment is furnished by the ethereal arrival of Sheryl Lee as Glinda the Good Witch, who offers some sage advice to a bruised and battered Sailor as he lies on the pavement after being beaten by a band of street toughs.

A pair of incidental verbal references to Twin Peaks also appear. In the car accident scene, we are shown “broken China doll” Sherilyn Fenn searching out loud for her “Bobby” pin before calling intensely and repeatedly for the driver, named “Robert.” Note that this scene occurs just before Sailor and Lula meet Bobby Peru. It seems unlikely that this many “Bobby” references in a few minutes of screen time aren’t intentional (This scene didn’t occur in the source novel and was invented by Lynch for the film). Another allusion occurs during the lovers’ first interaction with Peru when he quotes a 1930s blues song which includes the phrase “One-Eyed Jack’s,” although it is used here as a contraction rather than a possessive, misquoting a song lyric rather than conjuring the show’s across-the-border bordello.

In addition to the oblique references to other of Lynch’s works, several nods to other films are included. As Sailor recounts to Lula a previous sexual encounter with a brunette woman, he affectionately reassures her that “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes,” and a maimed clerk searches fruitlessly for his hand which, having just been blown off by Bobby Peru, is carried away by a dog, memorably recalling Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo. Marlon Brando is again evoked through the aforementioned phrase “One Eyed Jacks,” bringing to mind his Western film of the same name, and one cannot help thinking of Edgar G. Ulmer’s noir masterpiece Detour as Lynch’s camera watches Sailor and Lula drive top-down for miles through the desert air. These homages notwithstanding, it is unquestionably the spirit of The Wizard of Oz which presides over the entire affair, its iconic images permeating the very ether of Lula’s (and, consequently, the audience’s) view of their world. She likens her odyssey with Sailor to a trip down the Yellow Brick Road while anxiously envisioning her mother as the wicked witch who, supernaturally, sees her every move in a fortune-telling crystal ball. We see that she shares this fantasy with Sailor, who notes, after hearing of cousin Dell, “Too bad he couldn’t visit that old Wizard of Oz and get some good advice.” She replies, “Too bad we all can’t, baby.” But when crazy Jack Nance jarringly evokes Toto in conversation, Lula (and the audience) is unsettled. This unexplained knowledge of her inner world is felt as a violation, the first of several that will occur in Big Tuna. Soon Lula will click her red high heels together, wishing to escape the shame of being sexually assaulted by Bobby Peru while Marietta sports the curled slippers of the dead witch when sprawled athwart a vomit-filled toilet.

Pop Personas and Postmodern Problems

Erratic inserts of striking matches. Jarring intrusions of metal music. A barrage of egregiously unconcealed allusions to The Wizard of Oz, Elvis, and other monuments of American pop culture. These symbolic devices offer little clear exposition and typically confuse as much as they clarify. The road itself is a decipherable metaphor but these warped narrative elements seldom offer easily actionable wayfinding as Sailor and Lula drive further into a Lynchian heart of darkness. Some of Lynch’s most memorable characters inhabit this film and, though thoroughly drawn, remain scantly developed. Locations are abandoned before a cogent sense of place emerges. Realism is not the organizing principle of this universe. The film’s violence is so over the top that it seems to leap off the screen and grab the viewer by the throat. Sailor and Lula encounter characters, but we see only personae. Faces, hairdos, and bizarre rituals become our only impressions of the people who populate this world. Even the integrity of spacetime itself is dubious and, like anything and everyone, cannot be relied upon. The label inevitably thrust upon such a work (as it was in this case): Postmodern.

Even viewed through this lens, the awkward narrative disjunctions, tonal inconsistencies, flagrant cultural references, and the precarious balance of shallowness and excess seem to reveal little of the buried truth which postmodern literature purports to illuminate. This is because, as mainstream film was relatively late to the postmodern party and David Lynch was (as usual) at the head of the pack, his examination of the subject must acknowledge that this world has itself by now been influenced by the tenets of postmodernism.

The self-referential irony of the artistic and literary forefathers who cultivated the postmodern movement had, by 1990, been adopted as the official posture of hipness and sophistication by the culture at large. The postwar disintegration of traditional familial norms created an identity vacuum that drove the righteous rebellion of individuality. Because at its root this was a reaction to fear and insecurity, these forces prompted in the individual a need to outwardly express this distinctive selfhood. Unfortunately the base fear is not eradicated but inflamed, thus the drive toward actualization becomes the constant seeking of validation. Because the subconscious is not fooled, one becomes paranoid that the world is on to her, that she will be exposed as fraud at any moment. Accordingly, she must portray that which she knows she is not in order to deceive a world which might find her out. And how better to be what she knows she is not than to confidently say that which she does not believe? This is the essence of irony, the ultimate postmodern secret weapon.

In Wild at Heart, David Lynch employs the same detached irony to examine the disastrous effects of familial dysfunction that pervaded postwar American culture, particularly the first generation of children raised in the world of signal, noise, and image of electronic media. Rather than immersing the audience in its world and characters, Lynch keeps those elements remote to convey the loneliness and corruptibility of its inhabitants. In addition to the ironic sarcasm that handicaps interpersonal communication, Lynch also explores two further agents of social discord: perpetual cycles of trauma and abuse, and the reckless seeking of constant stimulation and pleasure.

Family Values

Sailor and Lula represent the survival of and coping with two distinct forms of childhood trauma. Sailor, we are told, “had no parental guidance,” and essentially grew from an orphan into an emotionally detached loner who has survived using his wits and weary-eyed persona of “cool” to keep the world at bay. This enables him to float above any risk of emotional vulnerability through quick verbal negotiation of obstacles. When this fails to safeguard him, he taps rich reservoirs of pent up rage to destroy any threats to his physical and psychological safety. His “wild” heart is surrounded by a traumatized child’s fortress of protection. Sailor’s need to constantly prove his strength and individuality is given respite in the safety of a world in which his only connection is the innocent and adoring Lula. The couple first appear in a public setting, and an altercation leads to Sailor’s violent killing of a man. Notably, Sailor lights a cigarette in a stereotypically “cool” posture to display his collectedness immediately after crushing another man’s skull (we learn he has been smoking since he was “about four”). The second time we see the couple in public, Sailor has just been paroled and wisely uses his verbal acumen to deflate a tense situation before it becomes ugly.

Sailor embodies the ironic postmodern individual who keeps the world at arm’s length, presenting a portrait of strength that is actually a reflexive aversion to being hurt or abandoned. Thus, the absence of formative familial belonging confers its own influence on Sailor’s development. The drive to build and maintain a relationship with Lula and ultimately the prospect of fatherhood are at odds with his obdurate resistance to surrendering his individuality, impairing his adaptability to the confines of the familial structure. This conditioned confusion is the root of Sailor’s tragedy, and it explains his adoption of the Elvis persona. To the postwar world, Elvis was the ultimate individualist, singularly occupying a position that defined cool to an entire generation.

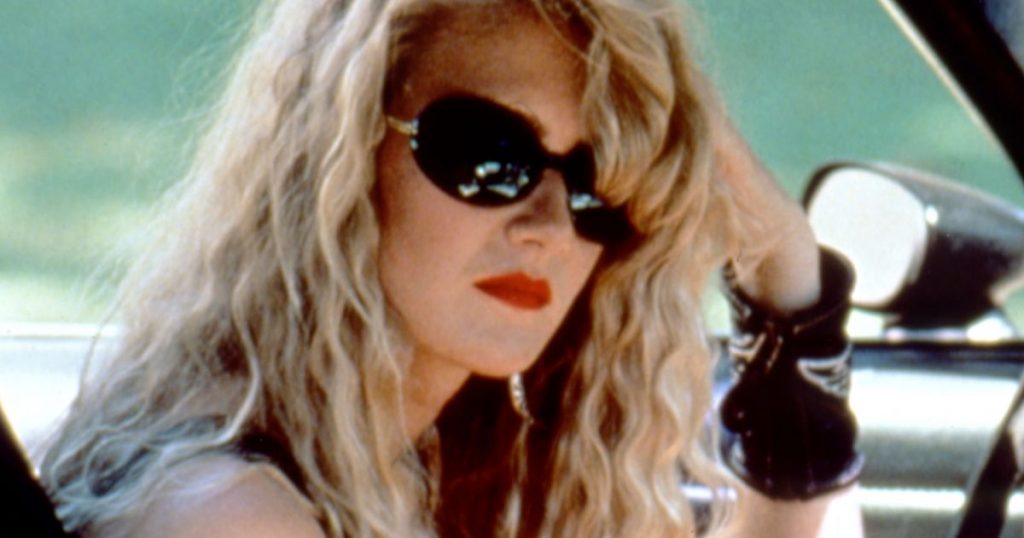

Lula, on the other hand, comes from a dysfunctional family, and her childhood was characterized by her mother’s control, traumatic sexual abuse, and the fiery death of her father. She muses that her father once noted how nice her breasts were, she loses her virginity via rape from an uncle, and her mother orchestrated the murders of both men. Lula’s suppression and eventual facing of these memories provide a key narrative arc of the film. Lula’s mother, Marietta, is fiercely centered on her own will and in no way obeys the prescribed boundaries of healthy relationships and decent society. The only true external object of her twisted affection is Lula, and the film draws several parallels between the two women, indicating that Marietta’s evil is rooted in psychosexual childhood trauma and that this same corruption may be gestating in young Lula.

As the death of Lula’s father and her avuncular rape occur before the events depicted in the film, both incidents are presented through Lula’s flashbacks. Interestingly, the visuals differ in several regards from her concurrent verbal relaying of the stories. This is clever filmmaking because it communicates to us 1) the nefarious truth behind the events, 2) that Lula knows these details, and 3) that she has suppressed them in her subconscious. Lynch again implements this directorial technique after Lula realizes she is pregnant with Sailor’s baby. This revelation brings an uncharacteristic anxiety which isn’t fully explained until we are shown, through another flashback, that she conceived a child as a result of being raped by her uncle, and that this pregnancy was terminated (most likely at her mother’s insistence). This event was demonstrably accompanied by intense physical pain and doubtlessly also by complex emotional and psychological trauma. Lula has not dealt with her familial history of abuse and murder. This explains her adoption of the Dorothy persona, a childhood fantasy into which she retreats as a means to make faceable sense of unprocessed trauma.

The absence of childhood development as part of a healthy and functional family unit is the root of much mental illness and plenty of social and psychological chaos. Throughout the film, Sailor and Lula provide one another mutual escape from a world gone to hell, and in spite of the difficult path orphanhood has bestowed upon Sailor, the film implies Lula may not be much better off for her upbringing than Sailor is for his. Perhaps it is no wonder these two survivors find meaning in one another. Sailor was never given a childhood and Lula was never allowed to grow up.

Wild at Heart’s narrative and character gallery display a world corrupted by the neurotic needs and psychotic effects of constant pleasure-seeking. A bizarre and mostly self-contained interlude introduces Lula’s Cousin Dell (Crispin Glover) as a neurotic, driven mad for want of constant Christmas. “Jingle Dell” then glues roaches to his anus and disappears from the film. At first glance this fascinating episode appears wildly out of place in the overall narrative, unless Dell is viewed as an embodiment of the excesses of modern society and the ceaseless demand for pleasure. He can’t bear a world without constant joy and stimulation, unaware of the irony that chronic Christmas would rob the holiday of its meaning. This contradiction is his tragedy.

Juana and Perdita Durango also implicitly demonstrate the transmission of devious impulses from one generation to the next. Juana finds ecstasy and sexual release in murder, and the fact that Perdita has grown up to become a henchwoman-for-hire like her mother implies that she, too, finds similar pleasure therein.

In Wild at Heart, David Lynch draws some of the most memorable villains of his career, but for the most part, they remain sketches. These are virtually the only characters we encounter, implying that this world is largely peopled with such grotesques. In fact, even the two heavies who occupy a significant position in the narrative (Marcellus Santos and Bobby Peru) are given no real motivations beyond the nature of employment and a simple enjoyment of carnage. Santos is a career criminal who ostensibly wants to eliminate Johnnie for his knowledge of his drug-running activities, but the two men are also clearly in some type of competition for Marietta’s attention. Bobby Peru’s extravagantly absurd persona provides a bit of comic relief while also disarming us. Thus, we are completely unprepared for his terrifying explosion of screaming menace in Lula’s bedroom. And Bobby’s death scene, perhaps the most memorable in Lynch’s entire filmography, manages to perfectly marry his shocking violence and cartoonlike hyperbole. Mr. Reindeer is suitably creepy, like a sinister grandfather with his cryptic fee of silver dollars dropped through the mail slot, though this odd detail remains essentially unexplained. Juana and Reggie seduce one another as their psychological torture of Johnnie becomes an act of foreplay, and the consummation of their desire is the pulling of the trigger. The bizarre linguistics and ritualistic setting are not developed, and the rest of their gang has virtually no bearing on the events of the film. Perdita herself seems to be simply a mechanism of the plot, and though her past relationship with Sailor is established, we witness nothing resembling any kind of chemistry between the two. What we have, essentially, is a world with no “normal” people. What appears at first to be lazy scripting or sloppy characterization is actually the fulfillment of Lula’s observation that “This whole world is wild at heart and weird on top.”

Deception and Delusion

In perhaps the film’s most memorable image, Marietta, upon realizing she has inadvertently sealed the fate of her lover, Johnnie Farragut, screams at herself in a mirror, having covered her entire face in red lipstick. Visually she embodies the Wicked Witch with the green face now replaced by startling red. But notice how Lula later addresses her own reflection in the mirror in the same way after being molested by Bobby Peru. This suggests that perhaps Marietta’s trauma is rooted in sexual abuse and that Lula may have the same psychosis brewing in her. Tellingly, both women share an attraction to Sailor (Lula says he reminds her of her daddy), and Lula’s repeated screaming the name “Sailor” is echoed tonally by her mother’s screaming of “Santos” when she realizes Johnnie has been killed. Both women also vomit at different points in the film, and a further connection is established between Marietta’s care of her lipstick and Lula’s detailed attention to applying her nail polish. These parallels imply that many of Marietta’s traits have been passed on to Lula, who is even able to rationalize her mother’s nefarious behavior by saying, “Maybe my momma cares for me just a little too much.”

Significantly, both mother and daughter refuse to face ugly and devastating truths, opting instead to block out painful memories (Lula) or submit to obvious lies to avoid guilt and sadness (Marietta). In this way, Lula’s childlike innocence in the face of trauma is contrasted by Marietta, who is consumed and tormented by the hellish aftermath of abuse. Marietta feels anxiously compelled to warn Johnnie of the “bad” thing she did in putting Santos on his trail, but she refuses to tell him over the phone. She insists on talking in person, but when she arrives, she cannot tell him then, either. She cannot bring herself to disclose what she has done, even lying about having involved Santos in the situation. Then, after Johnnie disappears, she quickly lets herself off the hook by believing Santos’s denial, drawing instead the implausible conclusion that Johnnie suddenly and uncharacteristically fled out of fear.

Sailor is Lula’s protector, shielding her from the ugliness of the outside world. In essence, he plays a role alongside her mother in keeping her a child. For example, when Lula is confronted with realities she cannot ignore, such as an inescapable cyclone of bad news on the radio, she begs Sailor to make everything right in the world again by finding the correct song. But when Sailor reveals that he has been keeping a secret from her, she is shaken and disturbed and begins experiencing a significant shift of thought and feeling toward him, saying “It’s just shocking sometimes when things aren’t the way you thought they were.” But as we have seen in her own flashbacks, many things have not been the way she “thought” they were.

As is often the case in the work of David Lynch, doubling and rhyming play an important thematic role in the narrative. Several incidental elements are issued in pairs, providing a sense of mirroring throughout the film. Typically, the second occurrence is in some way an outgrowth of or psychological deviation from the original. Sailor serves two terms in prison, the second being the inevitable result of the events following the first. He twice interrupts the natural flow of spacetime to serenade Lula, each time presenting an Elvis song, but his concluding rendition of “Love Me Tender” was foreshadowed in the first instance by Lula’s request (it is also made meaningful by his earlier promise that he would only sing it to his wife). Lula witnesses two car accidents, one following the first internal challenge to her relationship with Sailor and another driving to his second release from prison. Marietta has two romantic partners, her “legitimate” relationship with Johnnie Farragut and a more clandestine and mysterious one with Marcellus Santos. There are also two silver dollars dropped in Mr. Reindeer’s mail slot as payment for two contract killings, but only one (the killing of Sailor) was commissioned while the second satisfies Santos’s own wish to have Johnnie Farragut killed.

Characters are also often shown to mirror one another, usually highlighting their mutual occupancy of the same psychological realm. One such parallel is signaled by the sounding of the same ominous music cue when Marietta’s red face is first shown and when Sailor arrives at Perdita’s hideout. Like Marietta, Perdita’s hatred of Sailor is fueled by jealousy. We also learn that Perdita participated in the murder of Lula’s father, a further connection between the two women. An amusing tripartite is that at various points, three villains (Marietta, Mr. Reindeer, and Bobby Peru) all excrete into toilets amid the perpetration or arranging of violence or murder. Mr. Reindeer, seated on the toilet, even tells Santos on the phone, “that was good shit you sent over last week.” Interestingly, the initial scene (and primary catalyst moment) also involves a toilet. Marietta propositions Sailor after following him into a men’s room stall. When he refuses her advances, she calls him “shit” and says he “belong(s) in one of these toilets.” He calls her “white trash,” and we will see throughout the film that her attempts at class and sophistication are all a deceptive veneer, and that, like Sailor and Lula, she also wears a persona mask.

Trust and Betrayal

When Sailor tells Lula that he had not only previously worked for Santos, but that he knew her father, this implies that he knew certain details about her father’s death, and perhaps even that her recounting of the event was inaccurate. Immediately following this revelation, they happen upon the surreal car accident, a metaphor for her crashing emotions. As the life slips from the girl, Lula says, “She died right in front of us,” which, for Lula, is another awakening. Death has occurred in front of her before but, until now, she has refused to see it. When she can no longer ignore these tragic realities, she muses, “We’re really out in the middle of it now, ain’t we?” From here on, Lula’s communication with Sailor is more guarded. She is waking up from her innocence, becoming a bit weary and jaded like he is. Soon, Lula can’t tell Sailor aloud that she is pregnant, though she is able to write it down for him. She also apparently never shares with him the awful details of Bobby Peru’s visit, even after Sailor comes home drunk from a bar trip with Bobby. Perhaps as a result of her distance, Sailor also is less forthcoming, denying Lula’s correct intuition that he and Bobby are “up to something.”

Perdita and Sailor once “knew each other” and it is strongly implied they were romantically involved. Perdita scorns Sailor for his relationship with Lula and violates a friendly agreement when she lies to him about a contract having been placed on him. It turns out she is directly involved with the “execution” of said contract.

Marietta and Johnnie seem to take one another at their word but she betrays his trust by involving Santos in the pursuit of Sailor and Lula and then by lying about this involvement. Adding insult to injury, the very last moment of Johnnie’s life is occupied by the realization that Santos is behind his murder and that Marietta betrayed him.

Johnnie Farragut’s tragedy is his love for Marietta. She sends him to New Orleans to track down Sailor and Lula, and when Johnnie reasonably counters her hysteria about Sailor and the event with Bob Ray Lemon (which she orchestrated), she enlists Santos to undertake the same mission. By involving Santos, she inadvertently seals Johnnie’s fate. Johnnie is the one seemingly uncorrupted and purely good character in the film, and the subtle dread of his inevitable death infuses a profound anxiety into the fabric of the film. The very ether seems to cry out to him as “Baby please don’t go, down to New Orleans” plays continuously on his car radio. A sly clue that Johnnie himself knows this trip is a bad idea is that, upon seeing the Welcome to New Orleans sign, he says to himself, “The big N-O.” He’s telling himself not to go through with it; he knows he should turn around.

Marcellus denies that he will kill Johnnie and then describes to Marietta in specific detail how he will kill Sailor, but this is in fact the precise way Johnnie is murdered (we learn that the details of the hit were prescribed via Mr. Reindeer to Juana and Reggie). Every part of his commitment to Marietta is a lie. We’ve already learned he doesn’t actually respect her at all (following a phone call, he laughingly insults her to a colleague) but these lies solidify that Santos is merely looking after his own interests.

Crashing Symbols/The Medium Is the Mayhem

Inserts of striking matches and appearances of fire in general seem to presage instances of two types of pleasure: the carnal satisfaction of sex and the orgasmic release of murder and violence. The lighting of matchsticks transitions us to Sailor and Lula mid-coitus. The fiery death of Lula’s father (and no doubt that of her uncle) bring Marietta to an aroused cackle (the sound of which is a subconscious trigger for Lula). Furthermore, Johnnie Farragut is ritualistically murdered in a manner which clearly brings Juana Durango to her anticipated orgasm.

“Slaughterhouse” by speed metal band Powermad provides an interesting motif, becoming in essence Sailor and Lula’s de facto love theme. Significantly, though, the song initially occurs during Sailor’s rage-filled murder of Bob Ray Lemon during the film’s opening scene. The song, in addition to accompanying the intense passion of their love, is the soundtrack of Sailor’s violent impulse, the inner turmoil that fuels him.

Lula witnesses two car wrecks during the course of the film, and very nearly causes another. Each of these occur during moments of anxiety and confusion. She and Sailor witness the aftermath of what appears to be a single car accident on the side of a highway in the thick black of desert night. Lit only by car headlights, the surreal scene is a jarring intrusion into our tranquil wind-in-the-hair night drive, and its disruption of the narrative flow comes amidst and continues a series of important moments in Lula’s awakening. She witnesses a second accident en route to retrieve Sailor from prison, along with their six-year-old son, whom Sailor has never met. Internal apprehensiveness will soon find egress as the uneasy family tries to embark on a journey together.

When Wild at Heart was released, David Lynch had directed four feature films and had co-created one season of a wildly popular television show. It is notable, then, that radio seems to be the foundational transmitter of the film. Sailor is linked to a portable radio almost immediately in the motel room, and the car radio provides the soundtrack to their road trip journey. When the chaos of the outside world enters the radio stream, Lula experiences panic and can only feel joy again when Sailor twists the knobs to find “Slaughterhouse.” Though the film is infused with the specter of Old Hollywood cinema, the only movies actually being made or watched in this world are pornographic. And significantly, the only television set seen in the film shows wild animals viciously eating one another. These multimedia suggestions indicate that the purity of the golden age is over, that the radio has been corrupted by television, and the magic of filmmaking has tumbled into depravity and perversion.

Wild at Heart

The much discussed and often dismissed finale of the film has been a particular source of confusion and dissatisfaction among critics and viewers. Upon his second parole, Sailor is reunited with Lula and meets his son for the first time. The family unit drives uneasily until Lula stops the car and Sailor reveals he has decided to leave. Sailor offers his son a meretricious quote from Pancho to the Cisco Kid before walking (symbolically “riding”) into the sun. He is then surrounded by a gang of street toughs who he insults, prompting them to beat him up. Then Glinda the Good Witch (in the sublime form of Sheryl Lee) appears to him, advising him that if he is “truly wild at heart,” he will “fight for [his] dreams” and warning him to not “turn away from love.” Sailor then stands up, apologizes to the gang, and runs to rejoin his family who are stuck in a traffic jam. The film ends with Sailor’s foreshadowed serenading of Lula with Elvis Presley’s “Love Me Tender.”

This “happy ending” was not in Barry Gifford’s novel and was viewed by many, if not most, as a disappointing instance of an artist “selling out,” caving to the commercial demands of Hollywood. But in a film so free of Hollywood conventions (excepting those used ironically), this hardly seems likely. Sailor leaves Lula and their son because, although he claims to be doing them a favor, he is, in fact, still unable to submit to the family unit. It seems that trouble has always managed to find him, but actually it is the chip on his shoulder that causes him to provoke confrontation at every turn. As long as he remains in “self-protect” mode, he will always be fighting a world he sees as hostile and aggressive. Glinda reveals this to Sailor, and he finally understands that to be truly wild at heart, he must be vulnerable enough to let down his guard and go after what he loves. Upon this realization, Sailor comes to and apologizes to the ruffians, who promptly let him go without further incident. When Sailor drops the tough-guy façade, the world is not as violent a place anymore. He is finally free from the strictures placed upon him by his past and is able to join his family. Lula, who has ignored her mother’s warnings and gone to be reunited with Sailor, has thrown water on her mother’s picture. Thus, the wicked witch disappears and Lula, too, is free.

Summation

Upon close inspection and with the benefit of hindsight, Wild at Heart is clearly a unique picture in the filmography of a master artist who is singular in tpantheon of great directors. The film is a multifaceted time capsule of a particular moment when America was waking up from the illusions of its golden age to ruminate on what defines a hero and a villain in an increasingly complicated modern world. These themes, glossed in shiny sparkle and caked with grotesque grime, explore terrible and necessary truths of our age which are typically buried under such slick superficial surfaces. As he had done already and would do again many times over, David Lynch demonstrated in Wild at Heart that our fantasies will never be free of our nightmares until we learn to live at peace with ourselves and take care of one another.