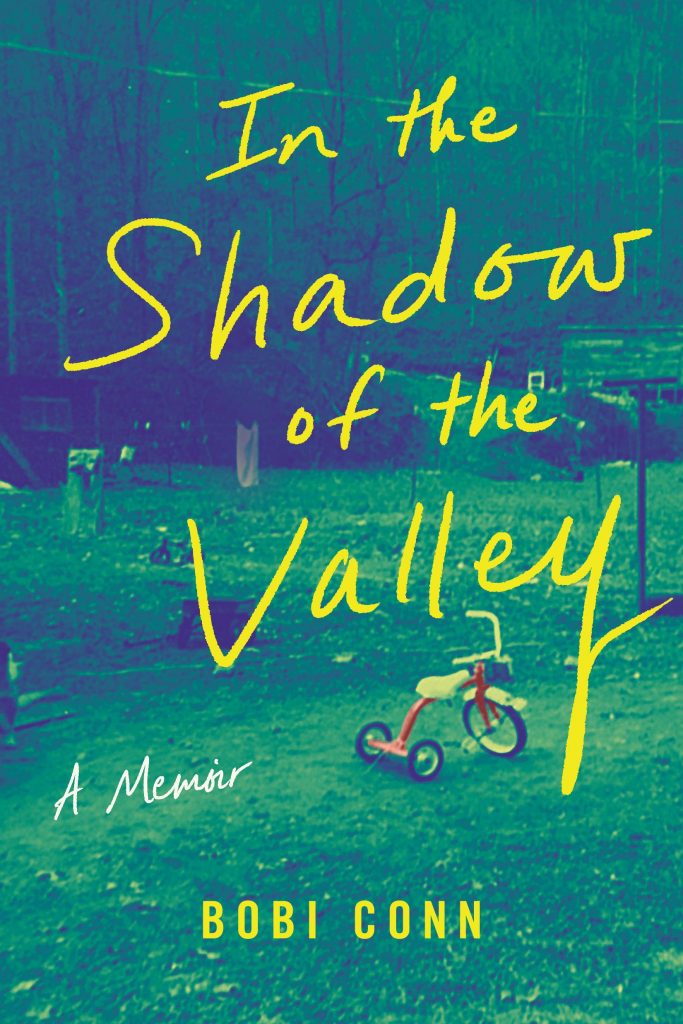

Like author Bobi Conn, whose memoir In the Shadow of the Valley is out now, I grew up in rural Kentucky. While our individual experiences coming of age in the Bluegrass state are unique and our own, the picture she paints, through telling her own personal stories, gives readers a glimpse of Appalachia that’s authentic and honest and raw. That authenticity rings throughout her work and, I imagine, will make their reading of In the Shadow of the Valley richer for it.

In the Shadow of the Valley focuses on Conn’s life growing up in the area in the 1980s, enduring abuse in her younger years and, later, navigating the worlds of her family and her peers in her white-collar job. Ms. Conn spoke with us recently about the story behind In the Shadow of the Valley, how she approached such a personal story, bringing authenticity to her experiences and the area where her memoir takes place, and what she hopes readers take away from the book.

FreakSugar: Before we get into the book itself, what can you tell us about your writing background and love for the written word?

Bobi Conn: I have loved reading for as long as I can remember, and it served as an escape for me – I threw myself into books as a child so I could go into a different world and be away from the trauma that unfolded around me, at least temporarily. I fell in love with writing when I was in middle school, and I wrote a little story for a class assignment. We had just read some stories from Greek mythology in my English class, and I was enthralled with those adventures. I think that was the first time I was excited to create a world through writing, and I was inspired by the characters and stories in the Greek myths. Ever since then, I’ve loved reading and writing because they are two sides of such a profound creative act.

FS: Your memoir, In the Shadow of the Valley, is a deeply personal book about your childhood and your relationship with Kentucky. What was the impetus for writing the book?

BC: I began writing this book in graduate school as a creative writing thesis. Since the beginning of my work on it, I wanted to tell my story (and the many stories within it) in a written form of Appalachian oral tradition. My goal with the book has always been to tell a story that I think is important, because it is a story of hope. I also wanted to create art from what otherwise were some pretty difficult experiences, because I felt that doing so would be a personal triumph and allow me to make a contribution to other people who would read and be touched by my story. And finally, I wrote this memoir to help address some of the misconceptions about Appalachia and to challenge the classist narratives that our society has yet to grapple with.

FS: As the book is so personal, how did you approach writing it? What was your process like for bringing your experiences to life for readers?

BC: I really had to put myself back into my childhood and young adulthood a lot while writing this book – neither of which were very pleasant. As every writer knows, you have to show, not tell, and to do that, I had to dig into the details I can remember through all of my senses. I had to be willing to face some ugly truths – sometimes about my family, but sometimes about myself – and that was really painful at times. However, it freed me as well. As I wrote, I realized that the act of telling our stories is an important step in defining one’s role as the storyteller of her own life. And in the end, as intimidating as it sometimes was to think of sharing my story so openly, I realized that I had claimed an agency that I never before possessed or even understood.

FS: I grew up in southeastern Kentucky myself and, while our experiences were different in many respects, the themes that you tackle in Shadow hit home for me and ring true. How did you look at bringing that authenticity in representing some of the real climates and concerns of Appalachia and her people?

BC: I’m still surprised sometimes when I hear from people who can relate to growing up in a holler, or the way they found comfort with their beloved grandmothers. And then there’s social issues a lot of us have faced, such as being first-generation college students, having our accents noticed (and often mocked), and both the internal and external barriers to the rest of the world. I think most of us from eastern Kentucky and the broader Appalachian region have a fierce love for the land, culture, and people – imperfect as we are. Far too often, the narrative about Appalachia has been shaped by those who aren’t from here and haven’t lived in this region, and so they depict the people as caricatures and the culture as broken. My story, at times, could be seen as confirming unpleasant Appalachian stereotypes, but that’s why it’s so important to delve into the full, complex reality of individual and collective histories. I believe in seeking understanding, and I wrote about eastern Kentucky with that goal in mind.

FS: Were there any particular parts of crafting the book that were more difficult than others, either because of the memories and emotions attached or just in how you wanted to write and present it?

BC: Writing about my young adulthood was actually the most painful because as I wrote, I saw that I had created so much difficulty for myself and made so many poor choices. It was hard for me to have compassion for myself at times, as I saw how ugly my life had been and how I contributed to that reality. I chose to be painfully honest about that part of my life, though, because I believed there had to be others who had made similar kinds of choices, and felt similarly about their own lives. I thought that if I told my story without hiding the parts of it I dislike the most, it would help others see that they’re not alone and that we don’t have to carry shame forever, like a punishment.

FS: Are there any memoirs or writers in general that informed to how you approached crafting your own story or have guided you in finding your own voice as a memoir author?

BC: I love Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt. I read that after I had written my graduate thesis (the first, short version of my memoir) and while I was reading it, I remember thinking that his life was so utterly terrible, and he rendered it with a beauty that made me want to stay in that horrible story. I then wondered how on earth he ended up able to write something so beautiful, and it struck me that the quality of his writing was the happy ending. I decided then that if I wrote more of my story, it had to be something beautiful, despite the ugliness it would include.

FS: Aside from enjoying the book, what do you hope readers glean from In the Shadow of the Valley?

BC: I hope readers come away from this book feeling like they have gained insight – into themselves, someone else, or the Appalachian region – hopefully, all three. And I hope that insight is accompanied by compassion. I wrote my story not with a desire to blame anyone for my life, or even for their own bad behavior, but to seek that understanding I mentioned earlier. Perhaps most importantly, I hope readers find themselves excited about their own stories, and feel the joy and power in telling them.

In the Shadow of the Valley is on sale now from Little A.

From the memoir description:

A clear-eyed and compassionate memoir of the Appalachian experience by a woman who embraced its astonishing beauty, narrowly escaped its violence, and struggles to call it home.

Bobi Conn was raised in a remote Kentucky holler in 1980s Appalachia. She remembers her tin-roofed house tucked away in a vast forest paradise; the sparkling creeks, with their frogs and crawdads; the sweet blackberries growing along the road to her granny’s; and her abusive father, an underemployed alcoholic whose untethered rage and violence against Bobi and her mother were frighteningly typical of a community marginalized, desperate, and ignored. Bobi’s rule of survival: always be vigilant but endure it silently.

Slipping away from home, Bobi went to college and got a white-collar job. Mistrusted by her family for her progress and condescended to by peers for her accent and her history, she was followed by the markers of her class. Though she carried her childhood self everywhere, Bobi also finally found her voice.

An elegiac account of survival despite being born poor, female, and cloistered, Bobi’s testament is one of hope for all vulnerable populations, particularly women and girls caught in the cycle of poverty and abuse. On a continual path to worth, autonomy, and reinvention, Conn proves here that “the storyteller is the one with power.”