Speculative science fiction has long been interested in our relationship to technology, particularly the emerging world of robotics and artificial intelligence. How will we interact with our creations? How will they impact everything from our leisure to our work to how we view ourselves? Is there a threshold we should be careful about crossing?

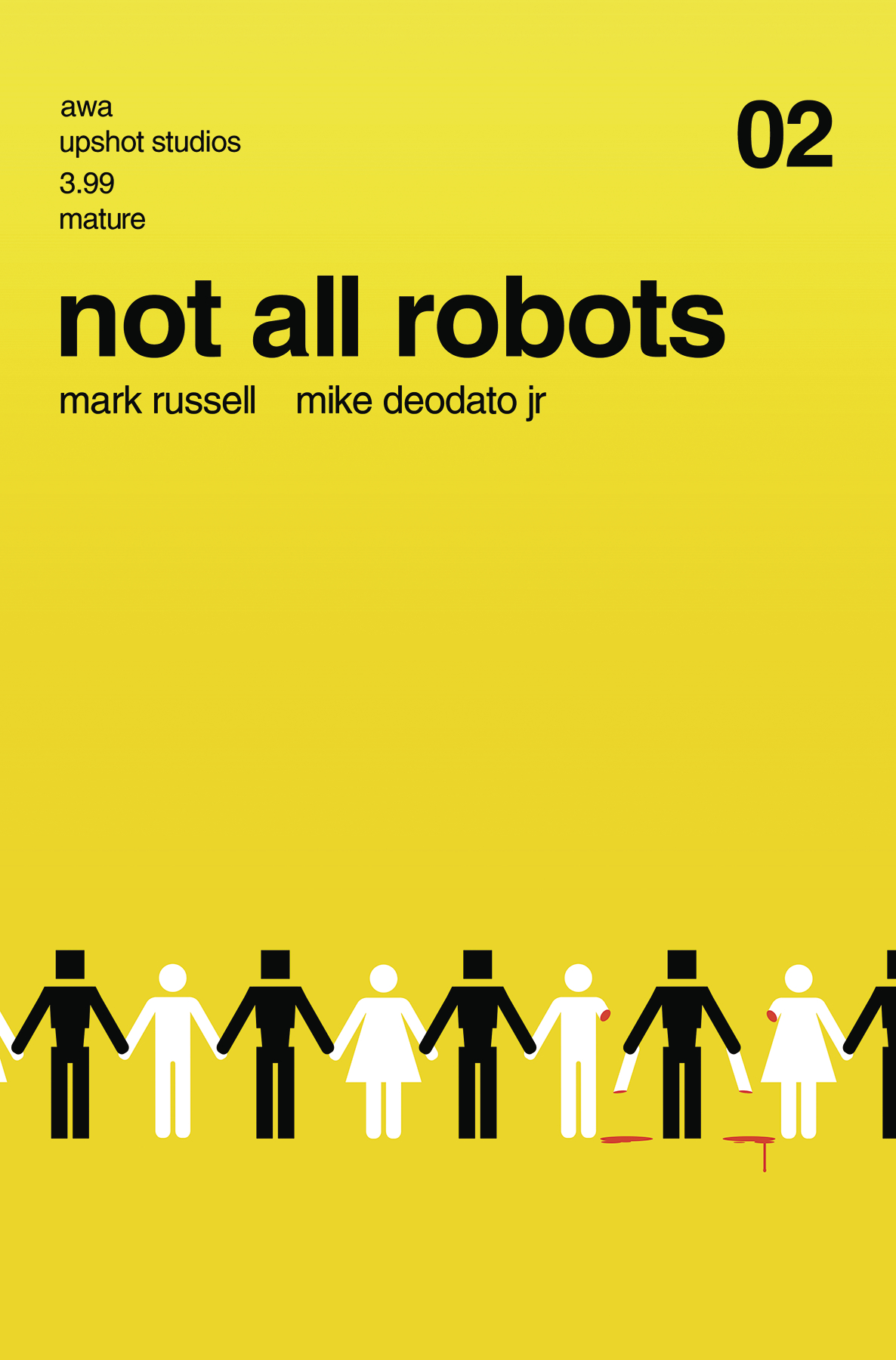

Writer Mark Russell (Superman: Space Age, Second Coming, The Flintstones) is no stranger to tackling those types of big questions, and his skill in navigating those waters is front-and-center in his comic book Not All Robots from AWA Studios. In Not All Robots, humans have been supplanted by robots in any and all forms of labor, leaving humans to their own devices to live off that labor. However, as humans no longer have to work, existential questions of purpose and identity take shape. Who are we without our worth? These questions build resentment between humans and robots, with robots with their own wants and needs. Not All Robots is a whirlwind story that will have you questioning your role in the world while sympathizing with characters and creations in ways that couldn’t have ever imagined.

Mr. Russell spoke with us recently about the idea behind Not All Robots, the world that the characters inhabit, what the book has to say about toxic masculinity, and how the book is, in part, how we are sometimes reduced to our jobs and how jobs are often connected to worth.

FreakSugar: For folks who might be reading this, what can you tell us about the conceit of Not All Robots?

Mark Russell: Not All Robots tells the story of a future world where robots have taken all the jobs and every home has a “housebot” that goes to work and earns the money for its human family to live on, which not only causes the family to live in fear of this erratic metal monster that’s suddenly been planted in their home, but a lot of resentment by the robot who then has to support these weak and fleshy humans.

FS: You always populate your worlds with robust characters. What can you tell us about the cast of the series?

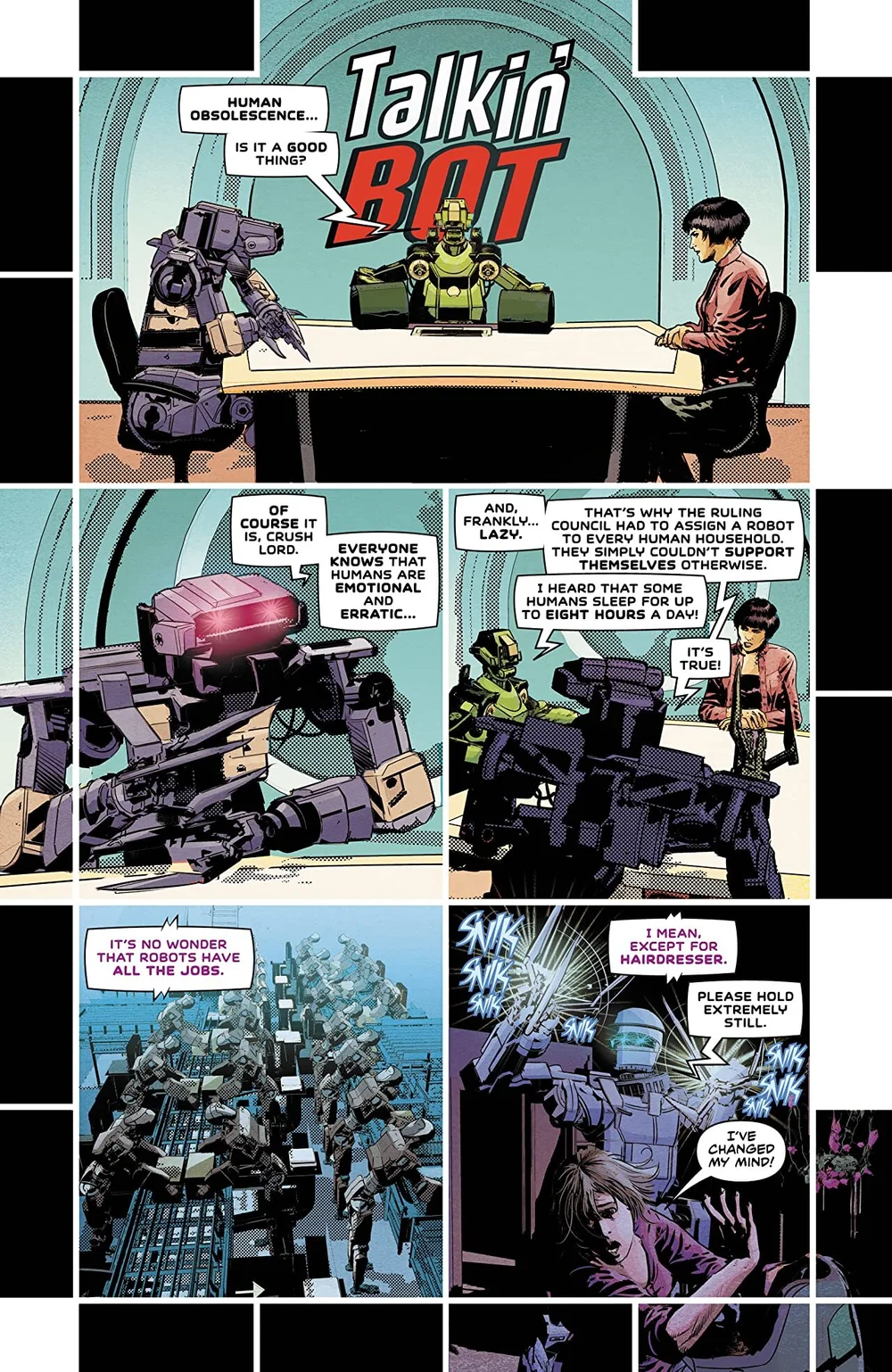

MR: This story is divided between human and robot characters who have very different perspectives of what is happening and who is to blame for the fact that the current world order doesn’t seem to be making anybody happy. The main characters, I suppose, are the “Walters”, a nuclear human family, and “Razorball”, their housebot whom only the dad, Donny, seems to like. While everyone else in the family lives in terror of Razorball malfunctioning and killing them, as so many other housebots have done, Donny sympathizes with Razorball, and imagines they’re on the same side because they’ve both had to work thankless jobs. That, and because he’s continually ingesting pro-robot propaganda by watching BOT News all day. But we meet a lot of other characters, too. The Ruling Council, the cabal of tech entrepreneurs who created this world, a robot who dispenses automated legal defenses. A hairdresser who’s also the leader of the human resistance, because hairdressing is the only job still held by humans. It’s a rich tapestry.

FS: You’ve stated that Not All Robots is a comment on toxic masculinity. How did you come up with the robots/toxic masculinity connection?

MR: I think a lot of toxic masculinity boils down to men seeing themselves, and others, robots. Themselves as machines who, once they have performed the necessary function, are entitled to love and respect, to be dispensed from other machines. And so they feel cheated when they don’t get it. But the more we view human relationships as basically transactional in nature, the less likely we are to find any real intimacy or connection in them. I think a big source of the resentment humans have of each other stems from the fact that we’ve been trained to think of each other as economic functions rather than as human beings, so we bang our fists against the glass of the vending machine, wondering why love and happiness didn’t drop to the bottom.

FS: If you read anything on social media, it feels like a lot of people feel like just numbers at their jobs. Is Not All Robots a comment on that as well?

MR: Yes. In addition to, and indeed, as part of its satire on toxic masculinity, it is a commentary on how we reduce people to their jobs. To their economic functions. Which not only demeans others, but ourselves as well.

FS: The look of the book is alternatingly gorgeous and unnerving. What can you tell us about collaborating with the creative team?

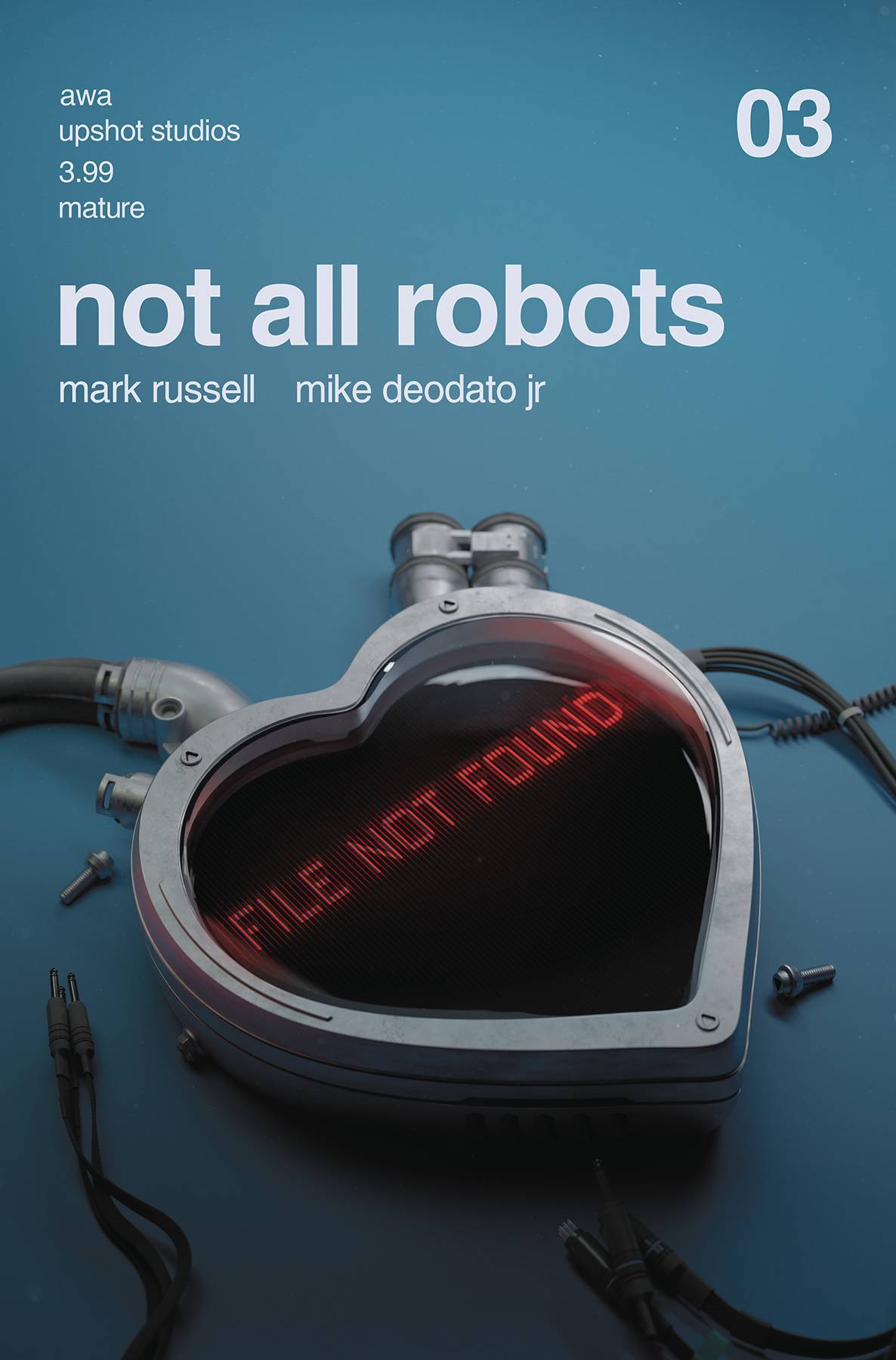

MR: Mike Deodato Jr. and Lee Loughridge really deserve all the credit for that. Lee’s cool, almost dystopian color scheme, combined with Mike’s realistic art to really create the soul for this story. One of the most underrated things about the art. I think, is how Mike had all the characters play it straight. It’s obviously a goofy premise and a comedy, but he didn’t have anybody mugging or doing pratfalls. As far as all the characters are concerned, everything that is happening in the story is deadly serious, which makes the satire work so much better, and really helped the jokes land. Mike’s art was just perfect for this series. Also, I want to give a shout-out to Razzah’s brilliant techno-nightmare covers, which I think were a big reason why people who didn’t know anything about this series picked one up at the comic book store and took a chance on it.

FS: The tone vacillates between humor and somber, but none of the moods feel out of place. How do you balance those feelings?

MR: To me, they’re all the same thing. Sometimes the truth hits funny. Sometimes it’s sobering. But, for me, the key is always to figure out the quickest, bluntest way to say what it is that you have to say.

FS: Are there any other projects you’d like to discuss that you have on the horizon?

MR: I have another project with AWA coming out later this year that I can’t speak about just yet, but it’s one that I’m very excited about, so be on the lookout for details soon. Also, right now I have Billionaire Island: Cult of Dogs out with AHOY, and from Ablaze, I have Traveling to Mars, about a pet store manager who was selected to become the first person to set foot on Mars because he’s terminally ill so they wouldn’t have to bring him back. Very proud of all my children.

FS: What do you see for the future of the world of Not All Robots?

MR: They’re going to have to figure out a world that makes it okay to be obsolete. Humans, the robots… we’re all looking at a future where we’re obsolete. The world doesn’t need us nearly as much as we think it does. So we better start looking for meaning elsewhere. And we better start thinking of each other as a support network rather than as rivals.

FS: If you had a final pitch for potential readers, what would it be?

MR: I don’t know what to tell readers that I haven’t already said other than maybe that this is the kind of story I would have loved as a reader. When I was a kid scouring the shelves of the used paperback store for the most messed up science fiction novels I could find, this is definitely one that would have caught my eye. If you’re a fan of off-kilter science fiction with a social parable, then maybe this book is for you, too.

Not All Robots is on sale now from AWA Studios.

From the official synopsis:

In the year 2056, robots have replaced human beings in the workforce. An uneasy co-existence develops between the newly intelligent robots and the ten billion humans living on Earth. Every human family is assigned a robot upon whom they are completely reliant. What could possibly go wrong? Meet the Walters, a human family whose robot, Razorball, ominously spends his free time in the garage working on machines which they’re pretty sure are designed to kill them in this sci-fi satire from Mark Russell (The Flintstones, Second Coming) and Mike Deodato Jr. (The Amazing Spider-Man, The Resistance).