There are so many misconceptions about the medium of webcomics, even from fans within the broader comic book industry. They’re sometimes regarded with scorn about their worth, as if the fact that they’re not print comics makes them somewhat less in value. However, anyone who has familiarity with webcomics knows what gross misconceptions those are.

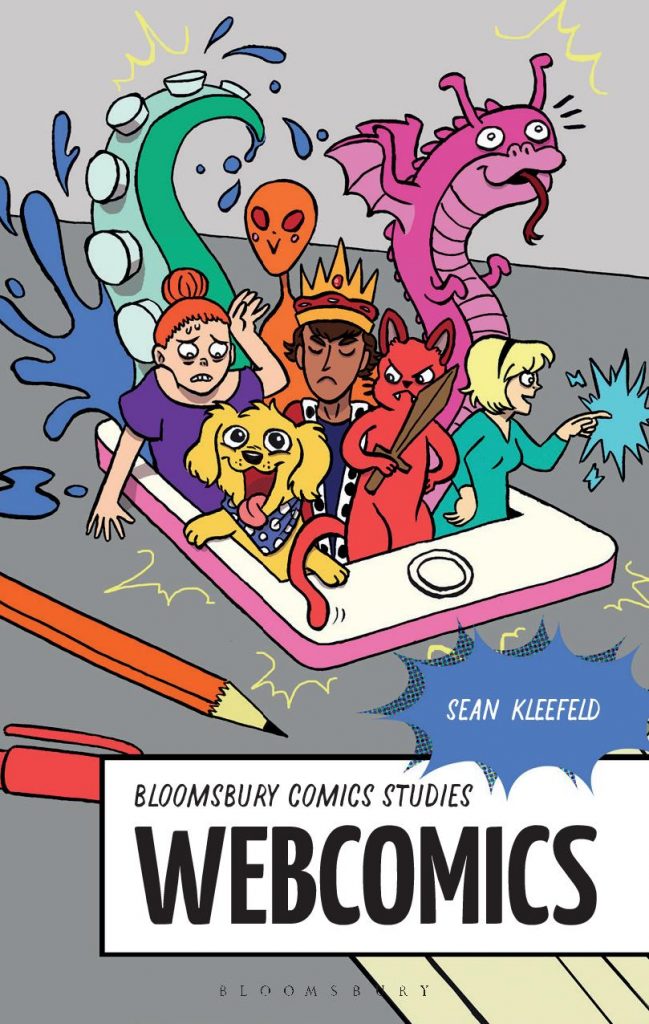

One of those people is author Sean Kleefeld, who has such a palpable passion for webcomics that it radiates off him. His joy for the medium translates to his scholarship, and he’s been reading and writing about all aspects of webcomics for over a decade. And in his wonderful new book Webcomics, out now from Bloomsbury, he gives readers a tour of the medium, looking at everything from its history to cultural contexts to the business of webcomics to different titles readers can check out.

Mr. Kleefeld was kind enough to talk to us about Webcomics, his background with and love for webcomics, the inclusivity of webcomics as a medium, and what he hopes readers take away from the book.

FreakSugar: Before we get into the book itself, what can you tell us about your background in comics general and webcomics in particular?

Sean Kleefeld: I’ve been reading comics as long as I can remember; I’ve got pictures of myself wearing Batman t-shirts when I was three. I started really getting into them when I was eleven and came across John Byrne’s run on the Fantastic Four. I was really taken by the characters and wanted to learn more about them and their world, so I started getting anything I could read with the FF in it. And if I wanted to learn about their “world”, well, that was basically the entire Marvel Universe. So I picked up as much as I could read about that. And if I wanted to learn about who created them, well, Jack Kirby practically invented comics! So I started reading anything I could about him and the other comics he created. So my circle of interest just kept expanding exponentially. By the time I was maybe 30, I was looking to learn everything there was about comics at all. So I try to read and research as much as I can. “Oh, look, a history of Russian comics!” “Oh, look, a biography of Gladys Parker!” “Oh, look, a 1942 research paper on how comics are made by a former Superman artist!”

With webcomics in particular, I started reading a few here and there in the late ’90s. My day job at the time was as a web designer, so I was already spending a lot of time online and just checking out what people were doing generally. I wasn’t seeing anything that really grabbed me back then and the early attempts at user interfaces were crude, and it was another five or six years before creators had started settling in to some navigation conventions that I felt were decent enough to give them my regular attention. What’s funny is that I recall not really reading any webcomic titles regularly until about 2003/04 and feeling like I was coming to the party really late. Five years later, I still wasn’t really seeing anybody talking about webcomics, so I started a column on MTV Geek about it. I’ve been talking about webcomics on various platforms ever since.

FS: Whether you balk at this or not, when I think of webcomics experts, I always think of you. What was the impetus for wanting to write Webcomics!?

SK: Thanks for the compliment! I started writing about webcomics generally because, essentially, no one else was. I mean, obviously, webcomic creators are conversing about them, but mostly in and among themselves with a lot the discussion being shop talk. Brad Guigar has written a ton about webcomics, but it pretty much all falls under the “how to” umbrella. The comics industry at large only seems to be interested in webcomics when there’s a print component – when a webcomic is licensed by a major print publisher, or when a notable print creator tries their hand at a webcomic. Much of my writing about webcomics, including this book, is me jumping up and down, waving my arms, and saying, “Hey, let’s talk about webcomics, too!” I’m hopeful that having an academic publisher behind Webcomics lets me reach an audience I might not otherwise reach.

FS: You include a quote from Tom Spurgeon on your website, who rightfully praises you as a clear and measured writer. What was your process like for writing Webcomics: the research, the process, and so on?

SK: My research started long before I actively started on this book. Obviously, I’d been reading webcomics for a while before, but my interest in figuring out how they’re made and who’s making them meant that I’ve been reading everything I could on the topic for years as well. By the time I formally started the book, a lot of it was swirling around in my head already. I’d also been writing a lot of shorter pieces for my blog and other outlets, so I’d even formalized some of my thinking around certain aspects of webcomics. I had a pretty good idea on the key points I wanted to hit in the book, and I had a pretty good idea of where to pick up good examples or quotes. My research queries then tended to be fairly specific. I wouldn’t look for “how long does it take to become established as a webcomic creator” but “where’s that breakdown that Jennie Breeden outlined about how it takes at least four years and what that’s like” for example. There’s more than a few instances in the book where I pull creator quotes from personal communications I had already had with them!

Nearly all of my writing is really the means, and not the end. I’m interested in just finding out about all things comics. In some cases, somebody’s already written a complete history or analysis or what-have-you, so I’ll just read that. In other cases, that hasn’t happened. So I do my own research and try to sort it out on my own. Writing is just the way I use to organize and structure things so I can make sense of that research.

FS: What kind of road map did you have in mind for the book when you first set out on writing it?

SK: The publisher, Bloomsbury, actually had a loose structure they wanted me to follow in the first place. It had to have a history section, they wanted some in-depth studies on 5-10 individual titles, etc. The way they had the sections pretty clearly delineated, it actually made it much easier for my writing process. It meant that I could approach it as almost a series of 5,000 word essays instead of one 80,000+ word book, so the overall project didn’t seem nearly as daunting. Which I realize is a stupid mental trick, but it still helped nonetheless. But it also meant that I could write it out of sequence. If I got stuck on any given section, for whatever reason, I could step away from it and just pick up on some other section pretty easily.

And since it’s academic publishing, they sent some of my early outlines and drafts around for a kind of peer review. “Would this be useful to you in a class” types of questions. I got some good feedback there of some additional sections to include. I also got some kind of nonsensical feedback as well, but that still ended up being useful in that it forced me to think about addressing some misconceptions and biases that some readers might bring to the table. And, again, that kind of topic delineation that the publisher already requested meant that I could retroactively add in whole sections without disrupting the book’s structure.

FS: Full disclosure: I’ve known you for a few years now from your work on FreakSugar. (We still need to meet in person one day!) Your passion for and knowledge of webcomics are beautiful things and I love reading your work. What is it about webcomics that pulls you in, not just the content but also the medium itself?

SK: Thanks so much, Jed! We definitely need to catch up in person… of course, after “meeting in person” is a thing people can do again!

One of the things I love about webcomics is, I think, one of their greatest attributes: a lack of gatekeepers. With print comics, you’ve got editors and publishers and distributors and all sorts of middlemen that can say, “I don’t think this story is marketable” and keep it from reaching an audience. And because historically, those middlemen are primarily older, cishetero, white men, a lot of voices get lost. Webcomics don’t have that. Regardless of who you are, you can put webcomics out there for anyone to read. And because the economics are so radically different, stories that aren’t financially practical in print can still find a sufficient audience online to earn a creator a living. One of the biggest complaints I’ve heard about webcomics in general is that the lack of gatekeepers means there’s no quality control and a lot of what gets posted is crap. But everybody’s got their own definition of what’s crap, so why force your ideals on everyone else? I love reading stories from/by/about voices substantially different than my own!

FS: Are there any webcomics in particular that you’re reading at the moment that you think we should be giving our bandwidth to?

SK: I’ll suggest a webcomic that I highlight in my book: Empathize This. It’s actually an anthology title with short stories written by the readers themselves, talking about specific instances where they’ve been marginalized in some way. They’re drawn by professional cartoonists and showcase the challenges and frustrations people feel when their lived experiences are ignored or dismissed because of who they are. They cover everything from racism to obesity to PTSD to autism to homelessness to… We live in a culture where you can keep yourself in a privilege bubble pretty easily, even unintentionally, and it’s not always easy to find people’s stories about why this “normal” thing for you might be a huge problem for someone else. The stories on Empathize This are very eye-opening and go a long way to enlightening people on issues that they might not have even realized were issues. So not only is it a webcomic that doesn’t get enough attention, but given the political climate, the very notion of spreading empathy is fantastically important!

FS: This is such a loaded, broad question that I don’t expect you to answer in a couple sentences, but what do you see as the relationship between print comics and webcomics? How can one inform or strengthen the other?

SK: I think this can go back to that gatekeepers issue. I think that a lot of the gatekeepers are/were sincere in their belief that certain types of comics wouldn’t sell or weren’t marketable, but what webcomics frequently show is that, no, these comics can sell, it’s just that the gatekeepers just don’t know how to market them in the first place. They have their limited view on who an “everyman” character might be or how relatable an event might be because they never personally experienced it. Now webcomic creators are putting work out there that very much does not fit the gatekeepers’ narrow view, and they have concrete numbers to show that these other stories can be just as, if not more, popular than anything else. Look at Raina Telgemeier’s Smile or Noelle Stevenson’s Nimona. Would those have even gotten published at all if they hadn’t proven themselves online? Those kinds of successes, I think, have started to open publishers’ eyes as to what’s marketable and I think the variety of work we’re seeing today from publishers today is at least in part due to what’s been able to be produced online.

FS: Following up on that, what do you see as the future of webcomics? The comics industry is a sometimes volatile one. How do you see webcomics impacting the industry? (This isn’t meant as a hypothetical question necessarily; I know it already is impacting the industry. Just curious on your thoughts on the matter.)

SK: We’re seeing now businesses springing up out of and around webcomics. Media companies like Blind Ferret, production and fulfillment companies like TopatoCo, and even publishers like Hiveworks and WebToons. Almost from jump, webcomics have been able to capitalize on technologies to produce small production runs of books or t-shirts or whatever that wouldn’t have been feasible a decade earlier, but we’re seeing now more businesses cater specifically to webcomic creators to help them build their platforms. Not just material goods, but services like tech support and marketing. I think we’re going to see more of that, and we’ll see webcomics more as an entire industry unto itself.

FS: Besides being entertained, what do you hope readers take away from Webcomics?

SK: I think a lot of people continue to broadly dismiss webcomics as garbage for people who can’t “make it” in print comics. That’s long not been the case, and I hope the book highlights to people just how many fantastic and impressive things are going on with them!

Webcomics is on sale now from Bloomsbury.

From the official book description:

The first critical guide to cover the history, form and key critical issues of the medium, Webcomics helps readers explore the diverse and increasingly popular worlds of online comics.

In an accessible and easy-to-navigate format, the book covers such topics as:

·The history of webcomics and how developments in technology from the 1980s onwards presented new opportunities for comics creators and audiences

·Cultural contexts – from the new financial and business models allowed by digital media to social justice causes in contemporary webcomics

·Key texts – from early examples of the form such as Girl Genius and Penny Arcade to popular current titles such as Questionable Content and Dumbing of Age

·Important theoretical and critical approaches to studying webcomics

Webcomics includes a glossary of crucial critical terms, annotated guides to further reading, and online resources and discussion questions to help students and readers develop their understanding of the genre and pursue independent study.