Seemingly contradictory, so much and so little is known about Margeretha Zelle, the one known as the famous and infamous Mata Hari. What is known is that she has the distinction of being one of the world’s first exotic nude dancers, gaining notoriety and fame across Europe. While claiming to be Indonesian royalty, her life met a less glamorous end than her claims belied, executed by the French for being spy and committing war crimes during the first World War.

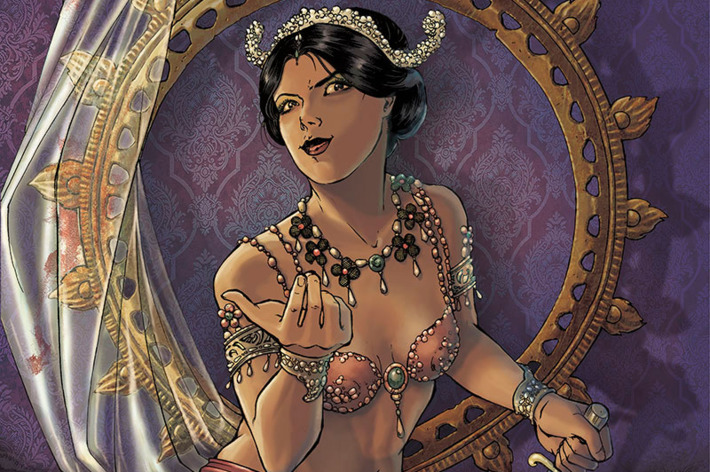

However, there’s a wealth of information about the figure that is not as well known, something that writer Emma Beeby hopes to change in her upcoming comic series Mata Hari, debuting Wednesday from Dark Horse Comics and Berger Books. Ms. Beeby spoke with me recently about the conceit of Mata Hari, why she decided to tackle the subject, and the balance in showcasing the good and the bad when telling Mata Hari’s tale.

FreakSugar: Thank you so much for the opportunity to speak with you. This is a gorgeous book!

Emma Beeby: You’re welcome, and thank you so much!

FS: For readers considering picking up the book, what is the conceit of Mata Hari?

EB: It’s the real life story of a seemingly ordinary Dutch woman who a century ago became famous as one of the world’s first ‘exotic’ nude dancers. She was adored as a star by the rich and powerful across Europe and claimed she was of Indonesian royal birth, but she’s best known for becoming a spy in World War 1, and being executed by the French as a double agent allegedly responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths. There’s a lot about her life that is less well known, that casts quite a different light on the supposed original femme fatale super spy, so this book is trying to show both sides.

FS: Where do we find Margaretha Zelle at the beginning of Mata Hari?

EB: We start with her in the last morning of her life, about to face her execution, having finished her memoirs – an attempt to secure her legacy and rebuild her reputation despite the case made against her. She really did write a memoir that was destroyed before it ever saw print, and we see that happen. The story then goes back to follow her starting to writing that lost memoir though her time in prison as she looks back on her life, while her accusers start to investigate the evidence against her. So we see both an idealised portrait and a damning one, and it’s really up to the reader to decide the truth.

FS: The history behind Mata Hari is a fascinating one. What was about it that drew you to telling her tale?

EB: I picked up a biography about her about seven years ago, and I was fascinated but not in the way I expected at all. I expected the sexy super spy, immoral and cunning and challenging ideas of female sexuality, and instead found a tale of survival and surprising success as well as a lot of tragedy. I went on to consume other biographies and articles and was really struck by how those writing about her struggled in working out how to judge her for the way she lived, how much blame she should take for the horrific things that happened to her, whether she was what she was executed for. It made me think – we’re a hundred years on and we still don’t know how to react to a woman like Mata Hari, whether to sympathise with her, or judge her. For me, it was as much about confronting all that as it was about telling her extraordinary life story.

FS: The marriage between the writing and the linework is hypnotic and gorgeous. What was the collaboration process like between you and artist Ariela Kristantina?

EB: We’ve only met once! We live in different continents and time zones. It’s almost all by email, with a lot of support from [Berger Books founder and editor] Karen [Berger] as well. The thing about something like Mata Hari is how much of what you see in the comic is real – real places, people, and events, and it all requires photo or painted reference or descriptions from the time. So, it’s a lot of work. I try to find as much as I can while writing to help Ariela, but we are often both looking for more sources. The script is definitely challenging, there’s different times in history, the main character at all these different ages, and a dance sequence going through the whole series, which needed its own approach. Ariela has done something stunning with all of this, there’s so much detail and beauty to it all, and she’s really made it so much more than I could have imagined.

FS: Following up on that, what was the research like constructing a story like Mata Hari? Were there things you discovered in your readings you’d never known about the woman?

EB: It feels never ending! I have two main biographies I’m drawing from, but new things have surfaced as I’ve written. A biographer I was in touch with recently sent me some information in translated letters from just before Margaretha becomes Mata Hari and tried to become an actress. She gave up because all the men auditioning her subjected her to the exact kind of casting couch treatment that we heard about in the Weinstein allegations. She refused them, and left Paris for a time, and was branded “difficult to work with.” It was a fascinating insight into her life, and an amazingly timely thing to come to light that I hadn’t otherwise seen written about. Also, for a woman who was supposed to unflinchingly use sex to get what she wanted. It was a telling insight.

FS: The book itself explores the various views toward Margaretha and who she was: what others saw her as and how she saw herself. Did your idea of Margaretha evolve or change while working on the book?

EB: I don’t know if it changed, but it certainly deepened to have to try to think from her point of view, which is not easy as she doesn’t think like most people (Most people don’t run away from their family to join the circus and then claim to be a foreign princess!). I think one of the things that I’ve come to think about more as I’ve been writing was the ugly colonial ideas of the time, and that her becoming Mata Hari was really a new fetishisation of the women of colour that she was passing as, and I didn’t want to whistle past that. Despite the time she spent in Indonesia, usually among women, this wasn’t something that seemed to give her a moment’s pause. Also she might have sought personal freedom, and her tale might highlight some horrific things about the way women are treated and viewed, both then and to this day, but she was not feminist in her ideas, even after those experiences, and quite against the votes for women suffrage movements that were happening at the time.

FS: Margaretha’s life took so many twists and labyrinthine turns. Did you two have any sort of mission statement that guided how you approached telling her story?

EB: We’ve had to leave a lot out, simplify, and play with timelines for a clearer sense of continuity while trying as much as possible to tell the true story. For me, a guiding point is to hold myself to account in staying balanced, to show the worst of her as well as the things that can easily make us sympathetic. I don’t think there’s much to be learned by idealising her. Also, I keep asking Ariela to make her look bad!

FS: What can you tease about what we can expect moving forward?

EB: Margaretha moved through some of the most beautiful and fascinating places and events of that period of time. We’ll see the beauty of Indonesia, Belle Epoque Paris, and go from living in great opulence to the fear of the Great War and the humiliating squalor of prison through her. Her life was extraordinary, and there’s a lot to see.

Mata Hari #1, written by Emma Beeby, with linework by Ariela Kristantina, colors by Pat Masioni, and edited by Karen Berger, goes on sale Wednesday, February 21st, from Dark Horse Comics.

From the official issue description:

Dancer. Courtesan. Spy. Executed by a French firing squad in 1917.

100 years on from her death, questions are still raised about her conviction.

Now, the lesser-known, often tragic story of the woman who claimed she was born a princess, and died a figure of public hatred with no one to claim her body, is told by breakout talent writer Emma Beeby (Judge Dredd), artist Ariela Kristantina (Insexts), and colorist Pat Masioni drawing on biographies and released MI5 files.

In this first part of a five-issue miniseries, we meet Mata Hari in prison at the end of her life as she writes her memoir–part romantic tale of a Javanese princess who performed ”sacred” nude dances for Europe’s elite, and part real-life saga of a disgraced wife and mother, who had everything she loved taken from her.

But, as she sits trial for treason and espionage, we hear another tale: one of a flamboyant Dutch woman who became ”the most dangerous spy France has ever captured”–a double agent who whored herself for secrets, lived a life of scandal, and loved only money.

Leading us to ask . . . who was the real Mata Hari?